- Insurance 150

- Posts

- The Importance of Floating Exchange Rates and Flexible Exchange Markets for Absorbing External Shocks in Developing Countries: The Cases of Colombia and Ecuador

The Importance of Floating Exchange Rates and Flexible Exchange Markets for Absorbing External Shocks in Developing Countries: The Cases of Colombia and Ecuador

How the case of Ecuador and Colombia teaches us about the importance of flexibility in the exchange markets during "good" and "bad" times.

Introduction

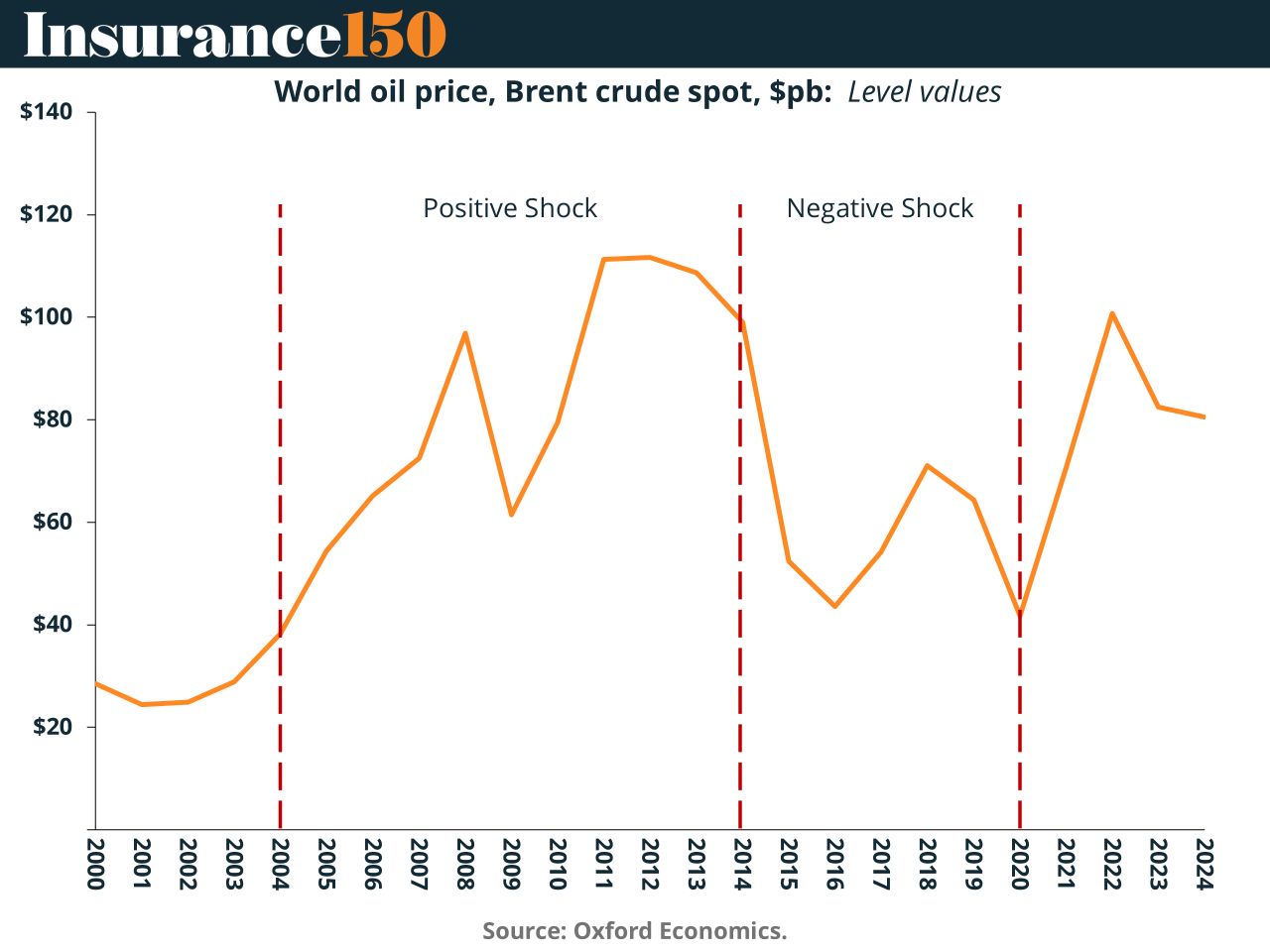

Exchange rate regimes are a critical policy choice for developing economies, particularly those exposed to volatile external conditions. Colombia and Ecuador are both heavily reliant on oil exports, making them structurally similar in their sensitivity to international crude oil prices. During the 2000s and early 2010s, both countries benefited from the commodity supercycle, with oil prices surging to historic highs and generating positive terms-of-trade shocks. Oil revenues became a significant driver of growth, fiscal revenues, and foreign exchange earnings.

However, when the oil supercycle ended around 2014 and prices sharply declined, both economies faced a negative external shock of similar magnitude. Despite their similar export structures and exposure, the macroeconomic responses diverged considerably—largely due to their exchange rate regimes. Colombia maintained a floating exchange rate, while Ecuador had been dollarized since 2000, effectively surrendering its nominal exchange rate as an adjustment tool.

This article analyzes the role of floating exchange rates and flexible foreign exchange markets in absorbing such external shocks, using the comparative evolution of key macroeconomic variables in Colombia and Ecuador. Drawing on the intertemporal models of small open economies and supporting empirical evidence, it argues that nominal flexibility through exchange rates is critical for allowing economies to adjust with less damage to real variables such as employment and productivity.

Theoretical Context

The canonical small open economy model suggests that countries should use external borrowing to smooth consumption during temporary shocks, and adjust consumption when shocks are permanent. This intertemporal framework hinges on a flexible exchange rate, which serves as a relative price allowing realignment of the economy without disrupting production or employment excessively. The Harberger–Laursen–Metzler (HLM) effect further argues that temporary terms-of-trade improvements should raise savings and strengthen the current account. In fixed regimes, this adjustment mechanism is blocked, often leading to painful real adjustments.

1. Foreign Reserves as a Shock Buffer

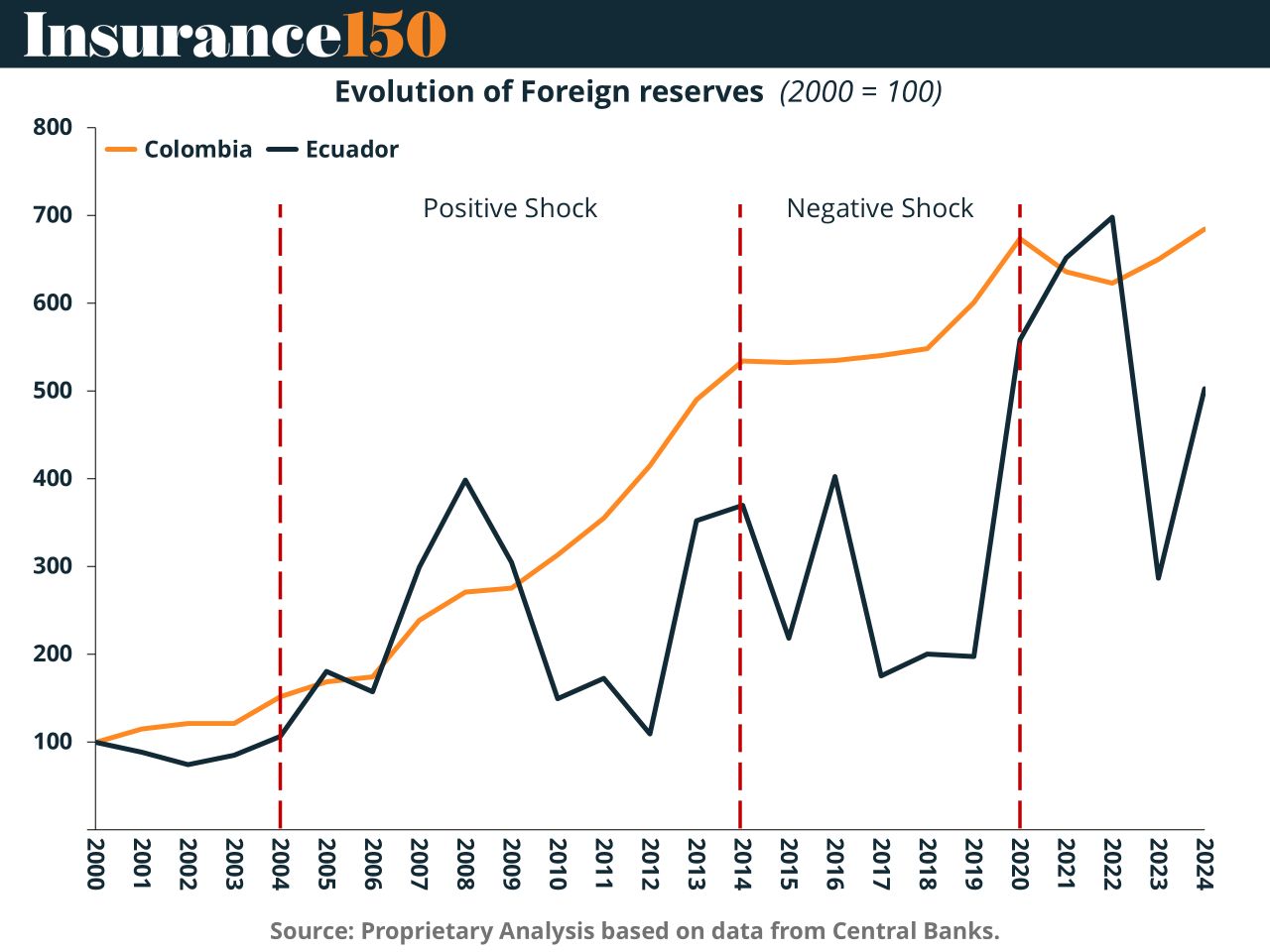

Colombia, with a floating exchange rate, displayed a stable and sustained accumulation of foreign reserves across the oil price cycle. This reflects its ability to adjust to capital flows and terms-of-trade changes through nominal depreciation or appreciation. Conversely, Ecuador—dollarized since 2000—experienced heightened volatility in its reserves, as it could not use the exchange rate to respond to external imbalances. Instead, it had to rely on reserve depletion or borrowing, leading to IMF support in 2019.

This aligns with the theory that in rigid exchange rate regimes, external adjustment falls on international reserves and external borrowing, increasing vulnerability during negative shocks.

2. Labor Market Adjustments: The Unemployment Trade-off

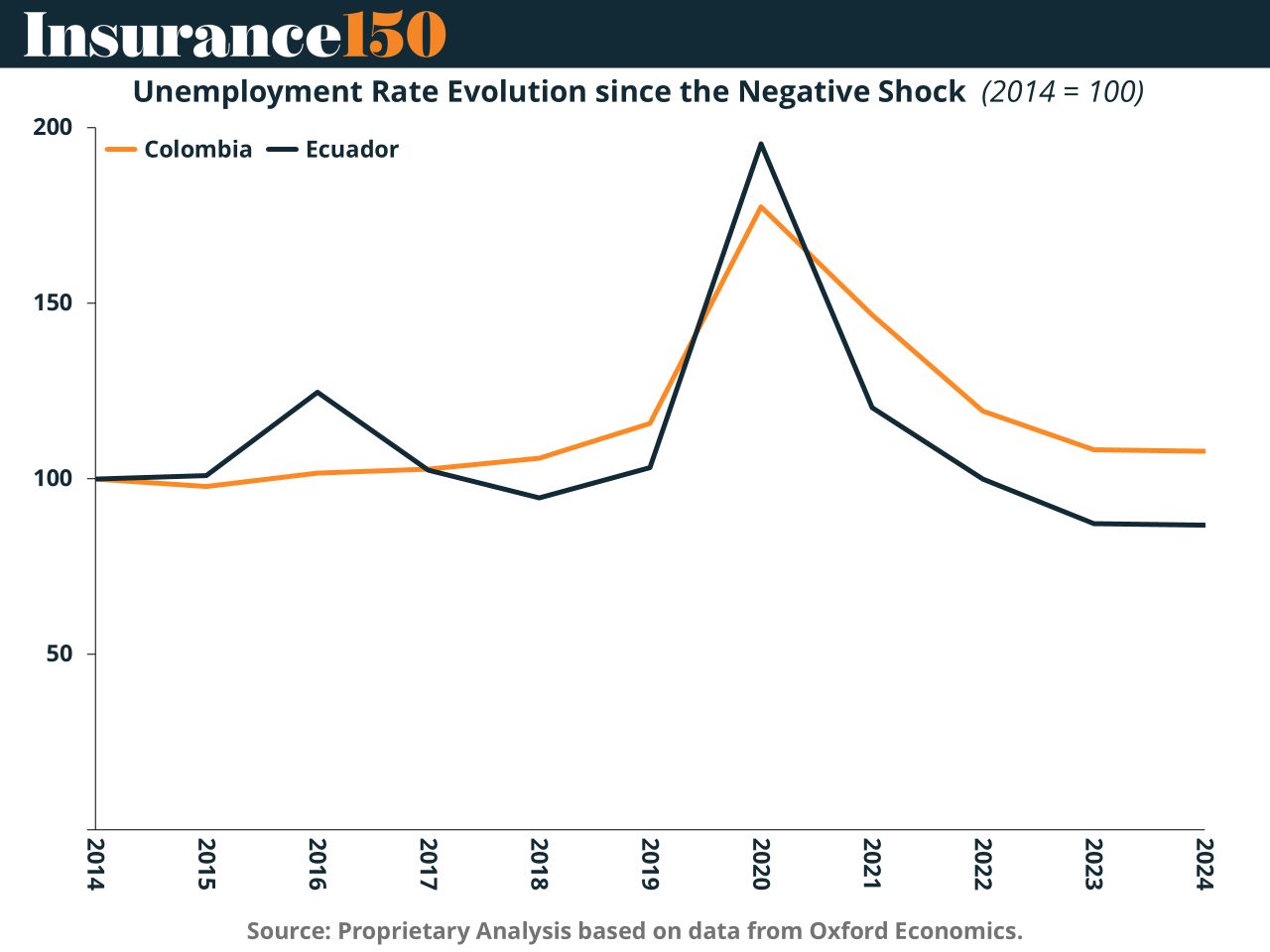

Unemployment dynamics in both countries followed the commodity cycle, but Ecuador’s labor market was significantly more volatile post-2014. When the oil boom ended, Colombia experienced a smoother adjustment, aided by exchange rate depreciation that softened the real impact on firms. Ecuador, unable to devalue, adjusted through job destruction instead. The result: more erratic and painful swings in unemployment.

This supports the view that in fixed exchange rate settings, real variables—employment and wages—bear the brunt of adjustment due to nominal rigidity.

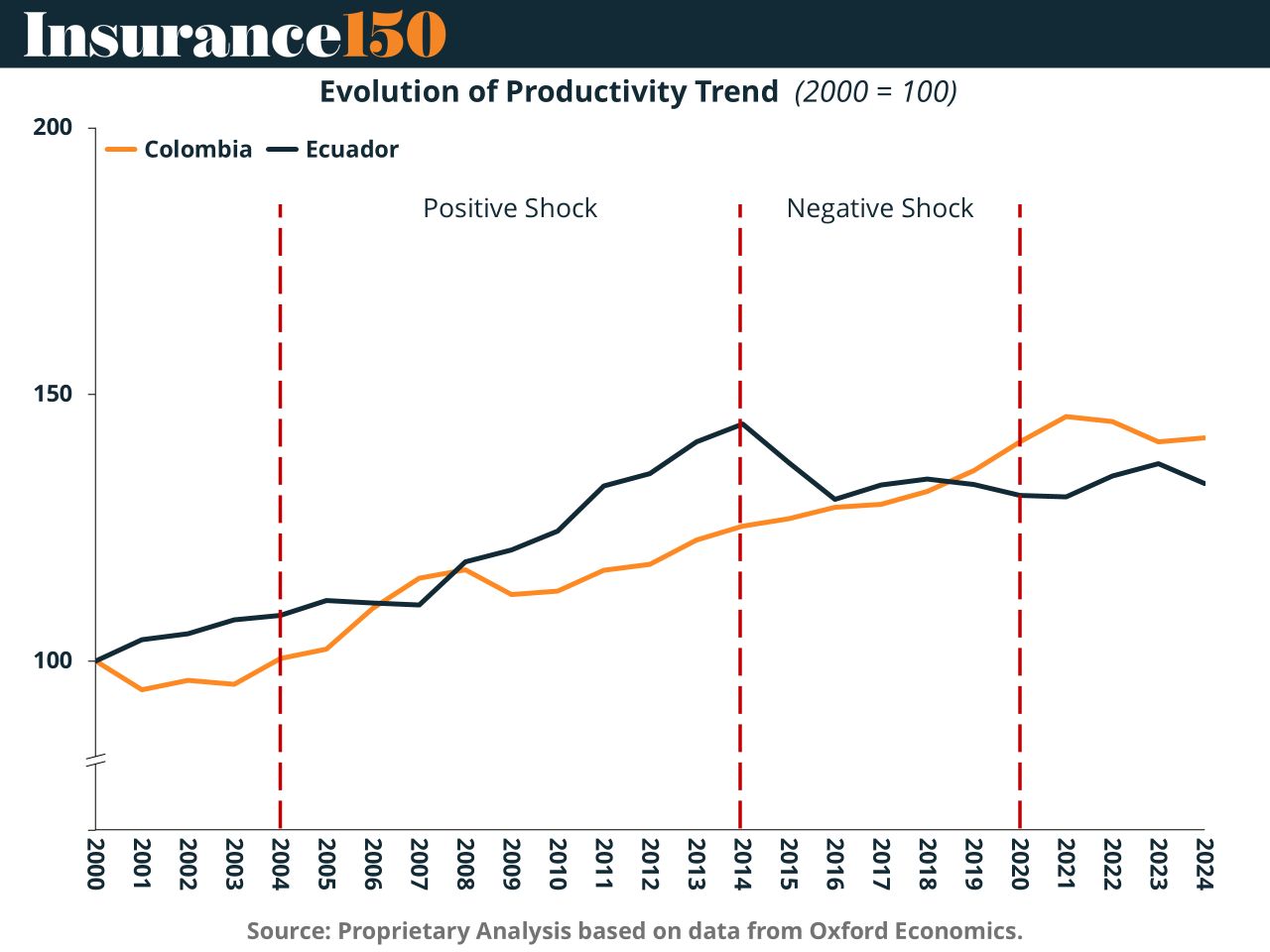

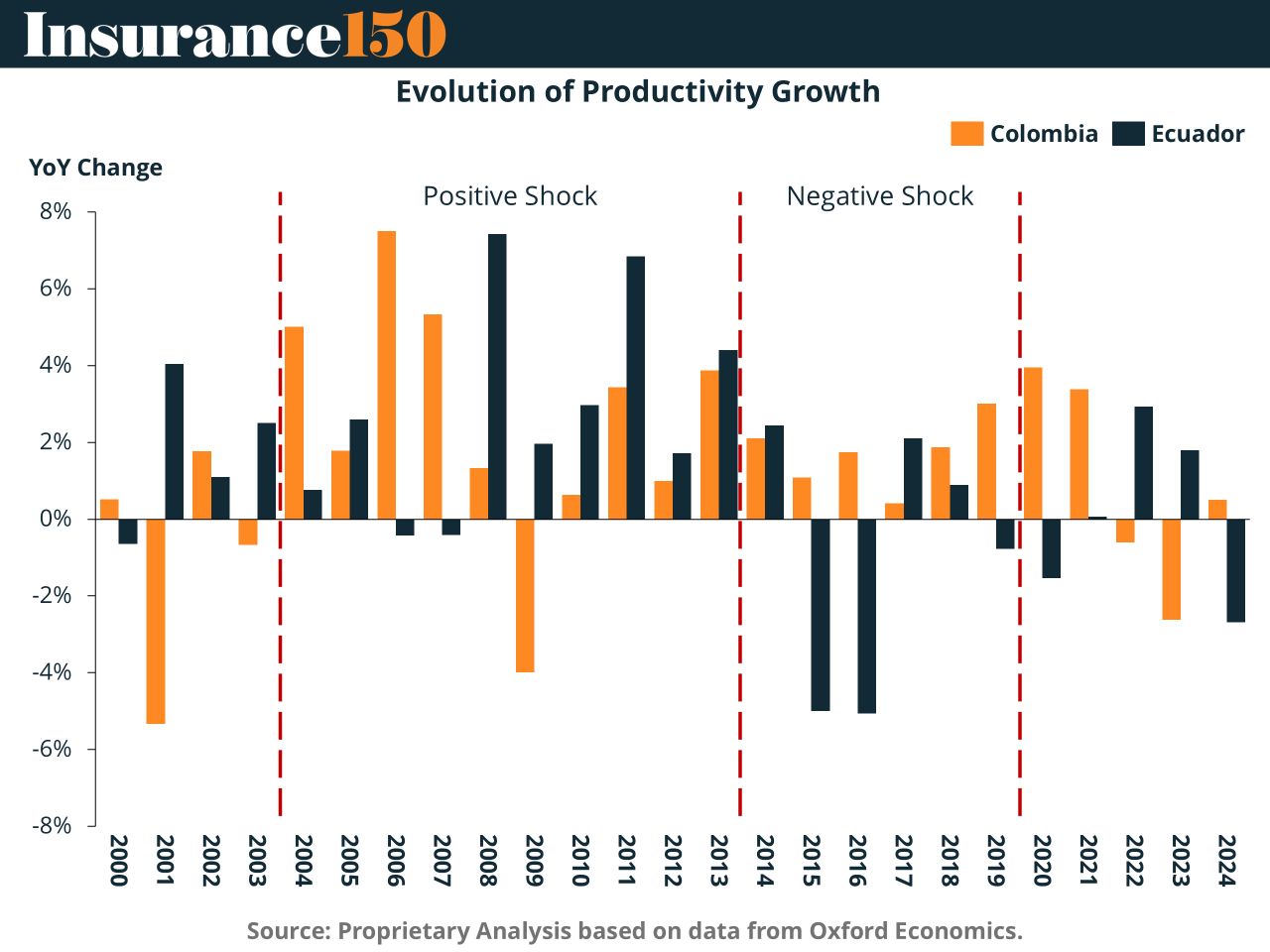

3. Productivity: Cyclicality and Structural Consequences

Productivity trends reveal another crucial dimension. Ecuador showed higher gains during the oil boom, arguably due to procyclical fiscal expansion financed by windfall revenues. However, these gains reversed sharply post-boom, with declining productivity as the economy struggled to adjust without the nominal exchange rate.

Colombia's productivity evolution, in contrast, was smoother and more stable across the cycle. Depreciation in bad times helped maintain external competitiveness and avoid abrupt contractions in tradable sectors.

This pattern illustrates the long-run costs of rigidity. Without flexible nominal tools, productivity becomes a residual variable subject to cyclical strain, impeding long-term growth.

4. Productivity Growth: Structural Deterioration under Rigidity

The decomposition of productivity growth reinforces the same story. Ecuador’s growth rate surged during good times but collapsed after the shock. In Colombia, changes were more muted, reflecting a more gradual and managed adjustment process.

Empirically, this result aligns with the macroeconomic stylized fact that volatility is higher in economies with fixed exchange rates, particularly when the external sector dominates the GDP structure.

Conclusion

The comparative experience of Colombia and Ecuador during the oil supercycle and its aftermath provides a compelling case for the benefits of floating exchange rates in developing economies. Flexible nominal adjustment via exchange rate depreciation mitigates the adverse effects of negative terms-of-trade shocks, preserving employment and sustaining productivity. In contrast, rigid regimes—especially dollarized ones—constrain policy space and force painful real adjustments.

For resource-dependent economies facing recurring external shocks, exchange rate flexibility is not just a buffer—it is a macroeconomic necessity.