- Insurance 150

- Posts

- US Inflation at a Crossroads: Tame Data, Political Pressure, and the Risk of Fiscal Dominance

US Inflation at a Crossroads: Tame Data, Political Pressure, and the Risk of Fiscal Dominance

Inflation in the United States has entered a paradoxical phase.

After the sharp post-pandemic surge that culminated in 2022, price growth has moderated substantially, yet remains stubbornly above the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. This apparent stability, however, masks deeper tensions between monetary policy, fiscal sustainability, and political incentives. The current environment is less about runaway inflation and more about the institutional credibility required to keep inflation expectations anchored.

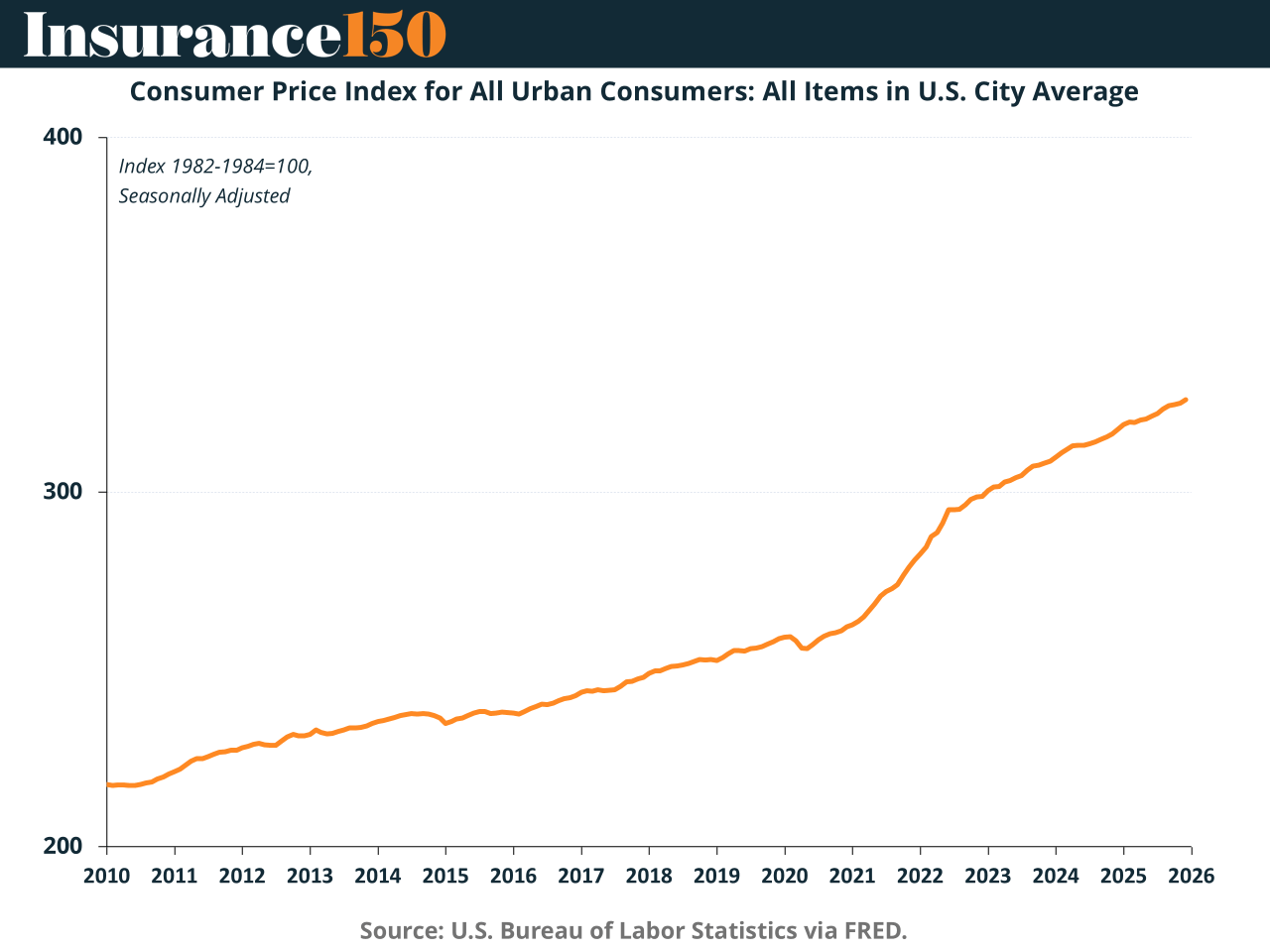

The long arc of US prices

Over the past fifteen years, the Consumer Price Index has followed a clear upward trajectory, with an especially steep ascent beginning in 2021. The acceleration after the pandemic reflects a confluence of supply bottlenecks, expansive fiscal policy, and accommodative monetary conditions. Although the slope has flattened since 2023, the level effect is permanent: the US price level is now structurally higher than in the pre-COVID era.

This matters because inflation is not merely about rates of change but about cumulative erosion of purchasing power. Even with annual inflation reverting toward 3 percent, households face a price level roughly 20 percent higher than in 2019, a reality that continues to shape political narratives around affordability.

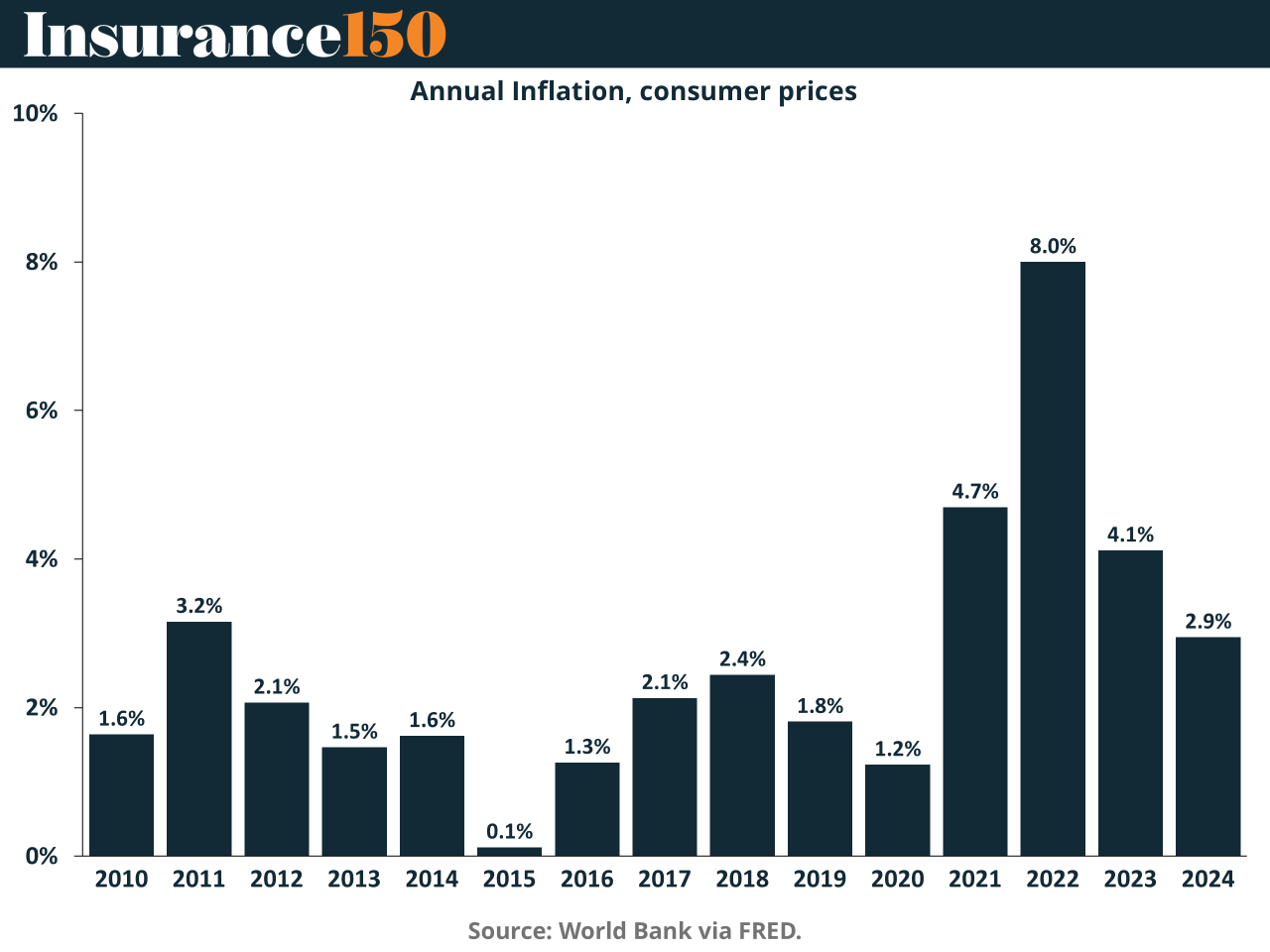

Annual inflation: normalization, not reversion

Annual inflation data reinforce the narrative of normalization rather than a return to the low-inflation regime of the 2010s. After peaking near 8 percent in 2022, inflation has fallen to just under 3 percent by 2024. This disinflation has been achieved without a deep recession, a rare historical outcome that speaks to the resilience of US labor markets and the effectiveness of restrictive monetary policy.

Yet inflation remains above the Federal Reserve’s target, raising the question of whether the last mile of disinflation will prove more difficult. Structural forces—such as deglobalization, energy transition costs, and demographic pressures in services—suggest that the neutral inflation rate may now be higher than during the pre-pandemic decade.

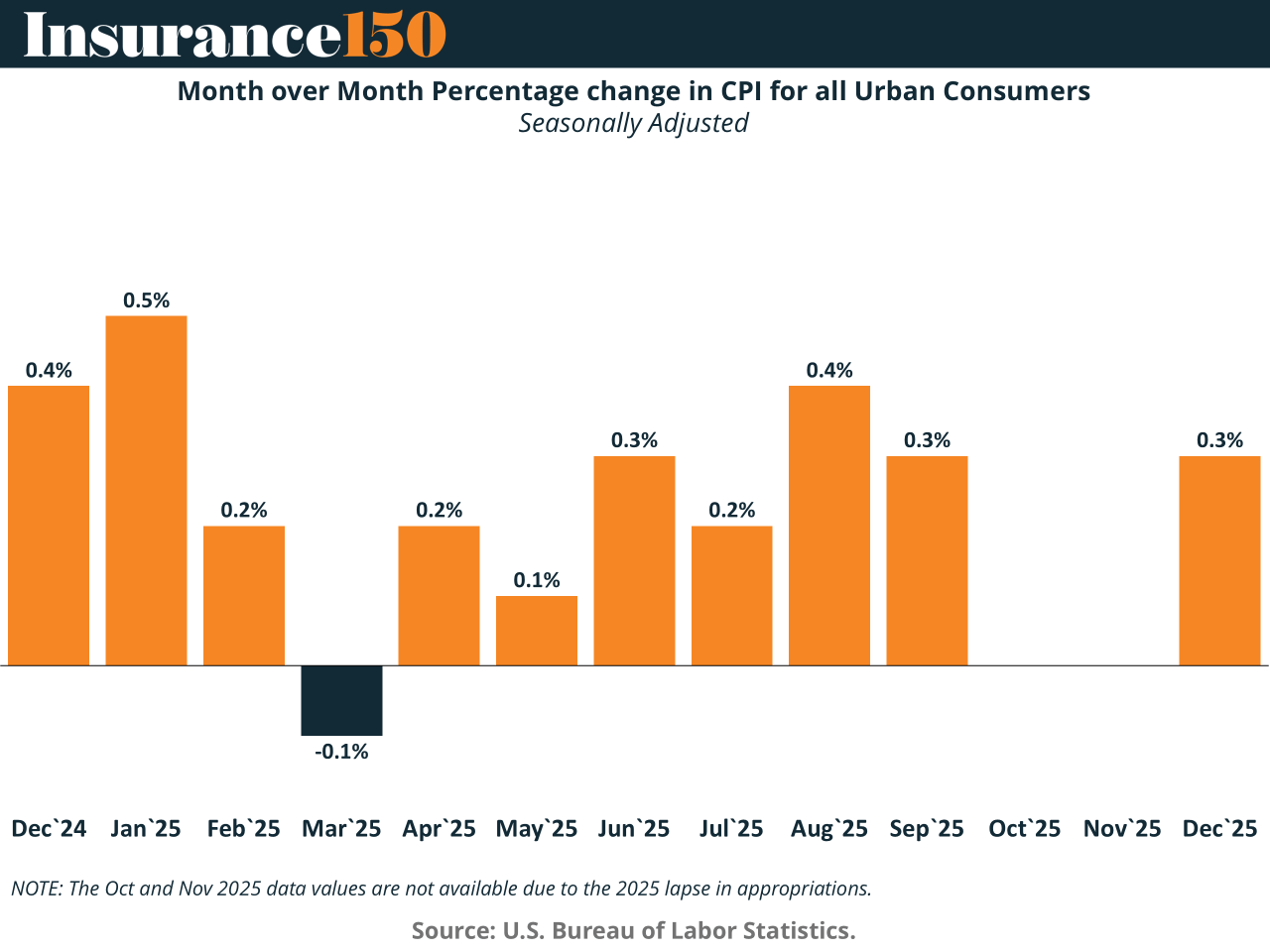

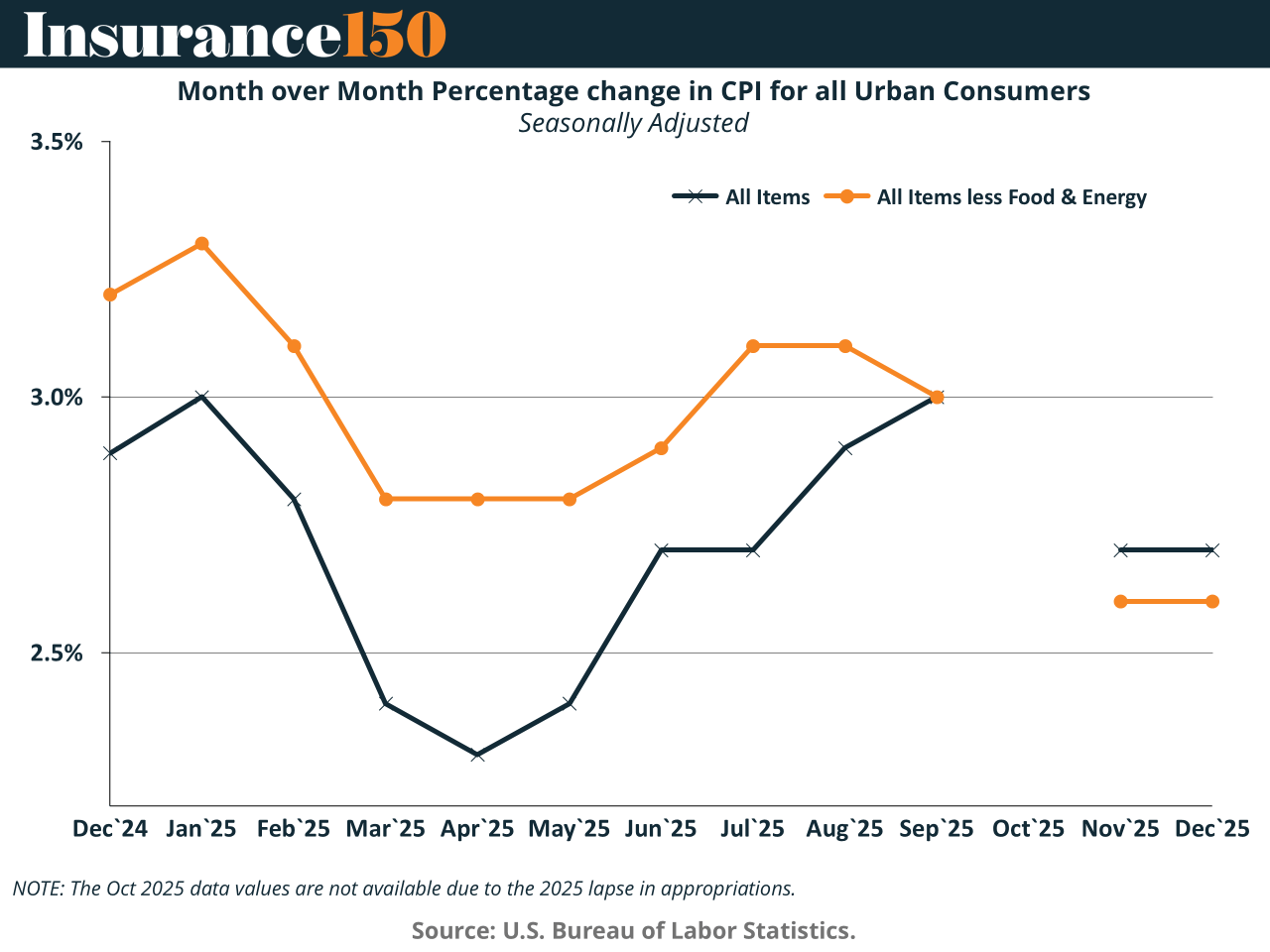

Recent dynamics: sticky services, cooling goods

Monthly data over the past year reveal a pattern of modest but persistent price increases, with a few notable soft patches. A negative print in early 2025 stands out but has not altered the underlying trend: inflation is running slightly above a pace consistent with the Fed’s target.

Crucially, the composition of inflation matters. Goods inflation has eased substantially, reflecting normalization of supply chains and softening demand for durables. Services inflation, by contrast, remains elevated, driven by shelter, medical care, and personal services. Shelter costs in particular continue to exert upward pressure, reflecting both lagged effects of earlier house price appreciation and structural housing supply constraints.

Core versus headline: convergence at elevated levels

The convergence of headline and core inflation near the 3 percent mark underscores the breadth of price pressures. In earlier phases of the inflation cycle, energy and food played outsized roles. Today, with commodity prices relatively subdued, inflation is increasingly domestically generated and service-sector driven.

This shift has important policy implications. Supply-side disinflation—through cheaper goods or energy—cannot do the heavy lifting anymore. Achieving further disinflation will require either a slowdown in labor cost growth, a deceleration in shelter inflation, or both.

Tariffs and the muted pass-through puzzle

One striking feature of the current inflation environment is the surprisingly modest pass-through from tariffs into consumer prices. Firms appear to have absorbed part of the cost increase through margin compression and cost-cutting rather than price hikes. This strategy has preserved market share but has also contributed to slower hiring and weaker real wage growth in some sectors.

However, this dynamic may not be sustainable. If margins remain under pressure, firms are likely to adjust prices eventually, potentially adding 1 to 1.5 percentage points to inflation over a year. Thus, today’s benign inflation prints may conceal future upside risks tied to trade policy.

Fiscal dominance: a latent threat

Beyond short-term price dynamics, a more profound risk looms: the erosion of monetary policy independence through fiscal dominance. Calls for lower interest rates explicitly to reduce the government’s debt-service burden signal a departure from orthodox central banking. When interest rate policy is subordinated to fiscal considerations, inflation control becomes secondary.

Historically, fiscal dominance has been more characteristic of emerging markets than advanced economies. In the US, the only comparable episode occurred during World War II, when the Federal Reserve capped bond yields to facilitate wartime financing. That arrangement ended in 1951, inaugurating more than seven decades of Fed independence.

The danger today is not immediate hyperinflation but a gradual unanchoring of inflation expectations. If investors come to believe that rates will be held artificially low to accommodate fiscal needs, longer-term yields may rise, not fall, as bondholders demand compensation for inflation risk. Ironically, this would increase borrowing costs, undermining the very objective of rate suppression.

Market expectations and policy credibility

Recent movements in breakeven inflation rates suggest that investors are alert to these institutional risks. While markets currently expect policy rates to remain steady in the near term, longer-horizon inflation expectations have edged higher. This divergence reflects confidence in the current Fed leadership’s caution, coupled with uncertainty about future political influence over monetary policy.

Two scenarios are plausible. If political pressure fails to sway the Federal Open Market Committee, policy continuity may prevail, albeit with elevated uncertainty premiums. Alternatively, if a more compliant leadership emerges, markets may react by pricing in higher inflation and volatility, raising term premia and tightening financial conditions independently of official policy.

Affordability and the limits of inflation policy

The political salience of inflation today is less about abstract price indices and more about lived affordability. Housing, healthcare, insurance, and education costs dominate household budgets, yet are only partially responsive to conventional monetary tools. Attempts to cap credit card rates, manipulate mortgage markets, or restrict institutional homebuyers address symptoms rather than structural causes.

In housing, the binding constraint is supply, shaped by zoning laws, permitting processes, and infrastructure capacity—areas largely outside federal monetary control. Similarly, energy prices are constrained more by global supply and investment incentives than by domestic regulatory fiat.

Conclusion: Stability requires institutions, not just data

US inflation is currently “tame” in a narrow statistical sense, but fragile in an institutional one. The disinflation achieved since 2022 is a notable success, yet it rests on the credibility of an independent central bank and a clear separation between fiscal and monetary objectives.

The greater risk to price stability over the medium term may not be excessive demand or supply shocks, but rather the politicization of monetary policy itself. If fiscal dominance were to take root, inflation would cease to be merely an economic variable and become a political instrument—an outcome that history suggests is rarely benign.

Sustaining low and stable inflation, therefore, will depend as much on preserving institutional integrity as on calibrating interest rates.

Sources & References

Deloitte. (2026). Weekly Global Economic Update. https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/economy/global-economic-outlook/weekly-update.html

Insurance150. (2025). Fiscal Dominance: Structural Debt Expansion, Monetary Growth, and Rising Risk Premiums. https://insights150.com/p/fiscal-dominance-structural-debt-expansion-monetary-growth-and-rising-risk-premiums

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI, December 2025. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average [CPIAUCSL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL, January 26, 2026.

World Bank, Inflation, consumer prices for the United States [FPCPITOTLZGUSA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FPCPITOTLZGUSA, January 26, 2026.